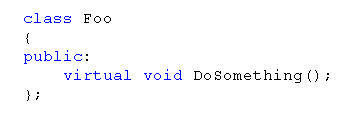

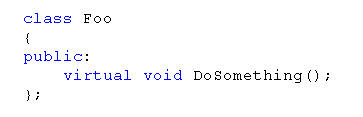

When’s the last time you saw code like this?

Did you:

- A) Think nothing of it?

Or.

- B) Say to yourself, "Oops – whoever wrote that goofed"?

It’s probably pretty obvious from today’s title that my answer would be "B".

The abstract reason for this is that Foo::DoSomething() violates (the spirit of) the Single Responsibility Principle.

This can be seen by thinking about who the customers (I say "customer" because "client" is a loaded term) are of public methods, and who are the customers of virtual methods.

The answer for public methods is easy: if you think of the class as providing a set of services, it’s the clients of the services, i.e. the users of the class. The answer for virtual methods isn’t much harder: it’s the implementers of derived classes.

In other words, public method declarations are an interface mechanism for informing clients about the services of the class; virtual method declarations are an interface mechanism for telling implementers about the behaviors of the class which can be specialized.

Understanding the Challenges of Public Virtual

A public virtual method is trying to serve two masters who might have conflicting requirements – this is usually a bad idea, as can be seen by the predicament that the poor gentlemen below has found himself in.

The practical reason for answer "B" is a flow control issue: execution flow never passes through the base class when a virtual method is called. This means that the base class has absolutely no ability to enforce common behaviors among the derived classes.

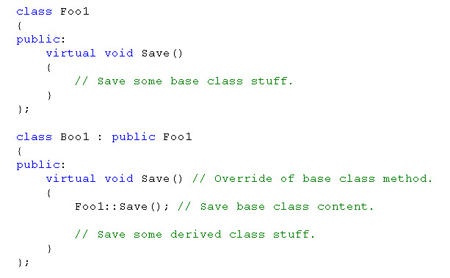

This in turn often leads to a set of rules that must be remembered in order to correctly override the base class methods. For example, when’s the last time you saw this save idiom:

Because Foo1::Save is virtual, the application requires the implementer of Boo1 to learn and remember to save the base class data.

This is a burden on the poor implementer (who often has to remember a different set of rules for each class) and a recipe for bugs when someone forgets something.

For More on How to Improve Engineering Design Flows:

- Why Does Anyone Need Polyhedral Formats?

- How SLDPRT and SLDASM are Effectively Used in Additive Manufacturing

- Why Your Apps Should Move to Support SLDPRT

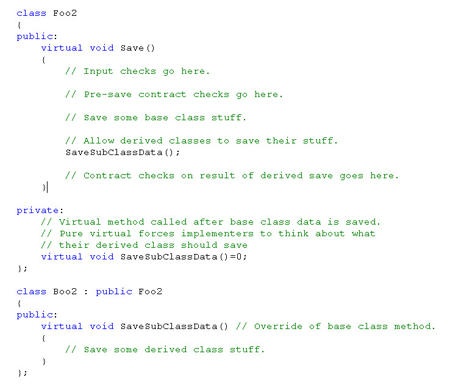

The way to solve this problem is to split the responsibilities between two methods: A public method that clients call and a virtual method that implementers override.

In contrast to the Foo1 example, there is all sorts of good stuff going on in Foo2:

- Implementers don’t need to remember to call the base class save – the base class saves its own data.

- Because flow passes through the base class, standard input checking can be implemented in the base class method.

- Pre- and post-operation contract checks can be performed in the base class method. This is especially important for the post-operation checks, because it can be used to ensure that implementers didn’t get subtle required behaviors wrong.

- The virtual SaveSubClassData doesn’t need a base class implementation, so it can be declared pure (forcing implementers to realize that the need to write a method) without confusing implementers with the "pure virtual methods are allowed to have implementations" subtlety.

- All of these attributes lead to cleaner, more robust code, and the underlying reason is that the different responsibilities are now properly segregated between appropriate methods.

Two subtleties:

1) You might have noticed that I declared Foo2::SaveSubClassData as private.

This is legal C++, and it’s preferred over declaring SaveSubClassData as protected.

The reason is that protected methods have a similar responsibility to public methods: they provide a set of services which derived classes can make use of. In other words, even derived classes should only call virtual methods through non-virtual base-class wrappers.

2) There is one exception to the above discussion.

The case where Foo is a pure interface class (analogous to a C# interface). By this I mean Foo has no data members, only pure virtual methods, and is used in a multiple-inheritance “mix-in” context to emulate the “implements” mechanism of e.g. C#.

The point of an interface class is that it’s a mechanism for client code to specify the services it requires; this is subtly different from the responsibility of public methods specifying the services the class supplies and corresponds to a single responsibility.

In particular, there’s no implementation code associated with an interface – control jumps straight to the implementer, which is exactly what happens with pure virtual methods.