It may be surprising to some that given the different target markets, there is an overlap between 3D visualization for engineering and interactive gaming. But whether it is to visualize a new actuator for a next-generation passenger jet, or build a post-apocalyptic cityscape populated with zombies, the goal is the same — enable human interaction. While the latter may appear less serious than the world of 3D engineering, the development costs for a console game are clearly very serious — Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 reportedly cost $50+M to develop plus another $200M in manufacturing, distribution and marketing, back in 2009!

Complexity is Driving Similarity

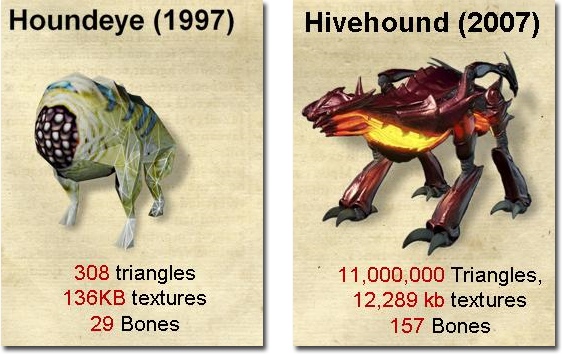

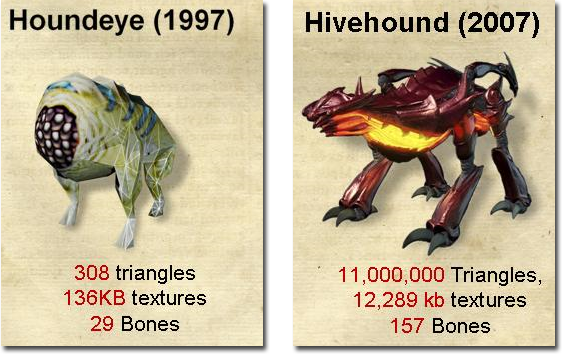

Steve Theodore, former Director at Bungie (Halo 3) and artist at Valve (Half Life), writing in Quora and Forbes describes the increasing complexity in gaming and helps put numbers around this complexity. Starting with a character Theodore did for Half-Life in 1997 using only 308 triangles, then a decade later, a similar character taking 11M triangles, to the requirements of photorealism now, the complexity in modern gaming is enormous, with triangle counts in the billions to render a scene.

Courtsey: Steve Theodore and Quora

This discussion of triangles highlights the overlap between visualization for CAD and gaming — it’s all about the triangle. Regardless of their origin, for rendering, both CAD and gaming work with tessellated data, using mesh surfaces before rendering the final scene. And for rendering, both CAD and gaming both use the same libraries, OpenGL, HPS, and DirectX.

Some techniques/tools are common to both. Or better said, some of the same techniques and tools are used in both CAD and gaming. One example is bounding volume hierarchy (BVH), where complex shapes (and groups of shapes) are represented using more simply described volumes. Both CAD and gaming can benefit from BVH as a way to ease collision detection and ray tracing.

Read More about 3D Modeling and Visualization with Spatial™:

But not all Goals Align

Both gaming and CAD use visualization to facilitate user interaction with a model, but each focuses on different goals. CAD focuses on precision and robustness, needing to ensure that all models work together with the same tolerances. The end goal is mathematical adherence to specifications, not caring about the speed of rendering.

Of course with polyhedral models, there is no meshing step, making the rendering phase very comparable to that performed in gaming, allowing polyhedral modeling rendering to achieve gaming speeds. But let’s not complicate the discussion.

In gaming, the focus is on speed of rendering and visual appeal, with precision often going out the window (many games suffer from occasional clipping, and overlapping elements). For gaming, rendering has to be done in real time, trading off between the number of polygons versus accuracy in order to achieve speed.

A good example of this dichotomy between modeling and gaming are spheres. A precise model of a sphere is defined by a simple equation and is, well, precise. In the world of games, a sphere has to be described as a mesh,and by definition, is far less accurate (and gamers don’t really care about the imprecision), but requires more data to be represented.

What will the Future Hold?

Predicting the future is always tough, but maybe as gamers push developers to achieve not photorealism, but cinematic presentation, it will push game developers to widely adopt the tools to achieve film-like special effects in real time (and remember we are entering the realm of 4K gaming).This requirement will push further development along the lines of OpenVDB. It is hard to imagine that modeling software developers will not try to piggyback on this work.