In modern engineering workflows, translating 3D models is not enough. Differences in modeling kernels, tolerances, and geometric rules can turn valid data into unusable models. Healing ensures translated geometry remains consistent, reliable, and faithful to the original design intent, making true 3D interoperability possible across CAD, simulation, manufacturing, and visualization workflows.

As engineering workflows become increasingly distributed, 3D models are no longer created, consumed, and finalized within a single system. They are shared across CAD platforms, simulation tools, manufacturing environments, and visualization pipelines, often developed by different vendors, built on different modeling kernels, and governed by different geometric rules.

In this context, interoperability is no longer about reading data correctly. It is about ensuring that a 3D model remains usable, reliable, and faithful to its original design intent once it enters a new environment.

This is where healing becomes essential.

At Spatial, we see healing not as a corrective afterthought, but as a foundational function of professional 3D interoperability. A translated model that merely displays correctly is not enough. If it cannot be edited, simulated, meshed, or manufactured without introducing errors, then the translation has failed—regardless of how visually accurate it appears.

Why 3D Model Translation Is Inherently Fragile

Most modern 3D modelers rely on boundary representation (B-Rep). In theory, this common foundation should make data exchange straightforward. In practice, it does not.

While B-Rep defines models using faces, edges, and vertices, each modeling kernel applies its own rules regarding:

- how surfaces must intersect,

- how much geometric deviation is tolerated,

- what level of continuity is required for validity,

- and how topology and geometry must align.

A model considered perfectly valid in one system can become invalid—or unusable—when imported into another. Small discrepancies in tolerances or continuity that were acceptable at the source can manifest as gaps, overlaps, or topological inconsistencies downstream.

This is why 3D data translation is fundamentally more complex than format conversion.

Much like language translation, correctness at the syntactic level is insufficient. The semantics of the target system, its geometric rules and modeling assumptions, must also be respected. Without this understanding, even standards-based formats cannot guarantee meaningful interoperability.

From Spatial’s perspective, this is a critical point: a translator must understand not only the data it reads, but the modeling kernel it writes to.

Tolerances and Continuity: Where Models Break

One of the most common sources of failure in translated models lies in tolerances and geometric continuity.

Different modeling systems apply different criteria to determine whether:

- two points are coincident,

- two edges are continuous,

- or a surface intersection is valid.

Some kernels require surfaces to intersect exactly at edges. Others allow gaps—within defined limits. Even among systems that tolerate gaps, acceptable sizes can vary significantly.

As a result, geometry that forms a clean, continuous surface in one environment may produce fragmented faces or open shells in another. These issues are often subtle, but their consequences are not: downstream operations such as boolean modeling, meshing, or manufacturing preparation can fail entirely.

This fragility is structural. It is not caused by poor modeling practices, but by legitimate differences in how kernels define geometric validity.

Effective healing must therefore reconcile these differences by adapting the data to the rules of the target system—without compromising the original shape or intent.

Units and Tolerances: A Hidden Source of Corruption

Units are often perceived as a trivial aspect of model translation. In reality, they are one of the most underestimated sources of geometric corruption.

Although most geometric modelers operate on unitless numerical values, CAD documents assign meaning to those values by defining a model length unit. This interpretation directly influences how tolerances are applied throughout the model.

If units are misinterpreted during translation, tolerances can be scaled incorrectly. A gap that appears negligible at one scale may become unacceptable at another, causing geometry that was once valid to fail kernel validation.

Healing processes must therefore correctly interpret units before attempting any geometric correction. Without this step, even sophisticated healing algorithms risk introducing new inconsistencies instead of resolving existing ones.

At Spatial, unit awareness is treated as a prerequisite for reliable healing. Correct tolerance interpretation is essential to ensure that geometric adjustments improve model quality rather than distort it.

What “Healing” Really Means in a Professional 3D Workflow

In professional engineering workflows, healing is often misunderstood as a corrective step applied only to defective models. In practice, healing plays a much broader role.

Some healing operations address clearly invalid data, such as topological inconsistencies that prevent a model from being interpreted correctly by a modeling kernel. Others focus on improving the overall quality of the geometry so that it behaves more predictably in downstream workflows.

In the context of 3D translation with 3D InterOp, healing is intentionally implemented as a black-box operation. It is exposed as a TRUE or FALSE option in the API, enabled by default, with internal logic designed to produce geometry that conforms to the rules of the target system. While additional control is possible through advanced configuration mechanisms, this level of detail is generally outside the scope of typical interoperability workflows.

For applications that require finer control over geometric quality, additional healing capabilities are available through the ACIS Healing APIs. These are commonly applied to existing geometry, or to geometry generated by modeling operations such as Booleans.

In such cases, the input geometry may be technically valid, yet suboptimal for certain uses. Boolean operations, for example, can legitimately produce sliver geometry depending on the nature of the incoming shapes. While this geometry is not incorrect, many downstream consumers, particularly simulation workflows, benefit from its removal.

Healing is not limited to making models valid. It is about making them better suited for their intended use, while preserving their original design intent.

Inside the Healing Process: How Model Quality Is Restored

Healing is not a single operation but a collection of complementary processes, each addressing a specific class of geometric or topological conditions.

Some of these processes are applied automatically during translation through InterOp. Others are available through ACIS Healing APIs when additional refinement is required.

Stitching

Stitching restores topological completeness by identifying and unifying coincident edges and vertices. Faces that should form continuous sheets or solids are sewn together so that the resulting bodies are correctly interpreted by the modeling kernel.

This operation is performed as part of InterOp healing and forms the foundation for all subsequent geometric operations.

Geometry Simplification and Design Intent Restoration

Imported models often contain geometry that appears analytic when displayed but is internally represented as spline-based surfaces. This frequently occurs with formats such as IGES, where even simple shapes are converted into spline approximations.

Simplification replaces these spline representations with their corresponding analytic forms whenever possible. A classic example is a simple cylinder. In its intended form, it consists of two planar faces and a cylindrical surface. After translation through certain formats, all three surfaces may be represented as splines, technically altering the design intent of the model.

Running simplification restores these surfaces to planes and cylinders, preserving the original intent while improving robustness, reducing data weight, and simplifying downstream operations.

While simplification is available as part of InterOp healing, it is not always enabled by default. Its value lies not in repairing invalid geometry, but in restoring semantic clarity to the model.

Gap Tightening and Precision Control

Gap tightening improves geometric precision by resolving small inaccuracies between adjacent faces, edges, and vertices. This is achieved by recomputing intersections or adjusting geometry so that entities meet within desired tolerance limits.

The goal is not to reshape the model, but to ensure that adjacent geometry behaves consistently under the rules of the target kernel.

Figure: The surfaces are extended and the intersection is recomputed based on extended surfaces.

Figure: The plane surfaces and the cylindrical surfaces snap together at the bold-faced edges as indicated by the arrows.

Figure: Control points of the two spline surfaces are modified so that the surfaces intersect.

Geometry Cleanup for Downstream Workflows

In addition to the core healing steps, several cleanup operations are particularly valuable for simulation and analysis workflows.

Removing small edges reduces unnecessary geometric complexity that increases data size and complicates intersection and meshing operations.

Removing sliver faces eliminates thin or degenerate faces that are technically valid but often cause instability in meshing and simulation.

Merge operations combine neighboring faces or edges that share the same underlying geometry into single entities. For example, multiple coplanar faces can be merged into a single planar face. This reduces topological complexity, improves robustness, and significantly benefits downstream meshing performance. These operations apply to all surface and curve types, not only analytic geometry.

Together, these healing operations improve the quality, clarity, and usability of geometry without altering its shape or intent.

Healing in Real-World Interoperability Scenarios

In real production environments, healing is rarely applied in isolation. Its role and its requirements vary depending on how the model will be used after translation.

In CAD to CAD workflows, healing determines whether a model can be edited reliably. Operations such as filleting, shelling, or boolean modifications place strong demands on topological consistency and geometric continuity. A model that looks correct but contains hidden gaps or inconsistencies will quickly fail under these operations.

In CAD to simulation workflows, the tolerance for geometric imperfections is even lower. Meshing algorithms used in FEA or CFD are extremely sensitive to gaps, overlaps, and poorly defined intersections. Without effective healing, mesh generation may fail entirely or produce unreliable results that compromise simulation accuracy.

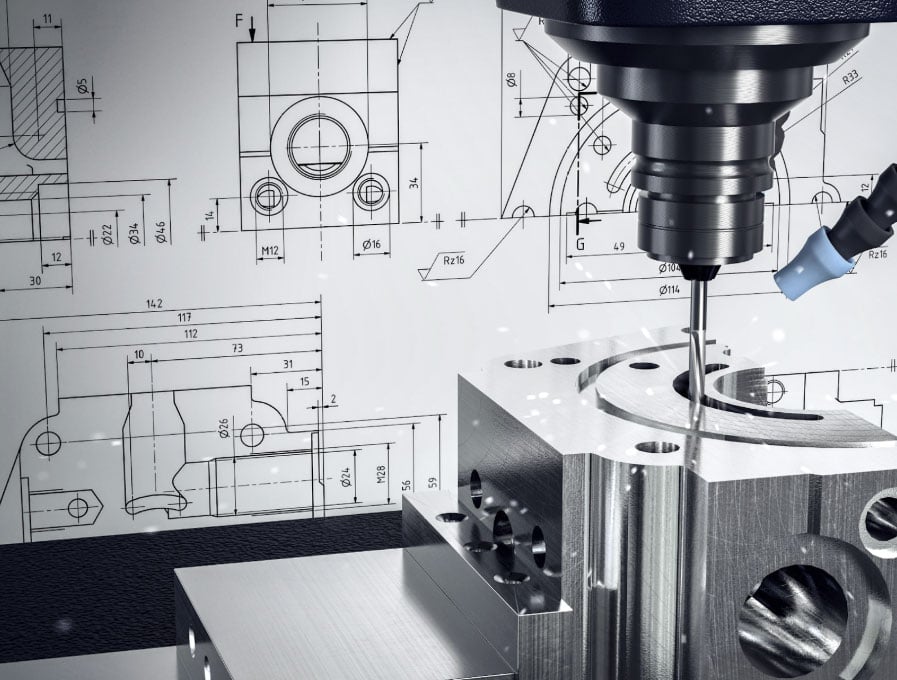

Manufacturing workflows introduce a different set of constraints. CAM systems rely on precise geometry to generate toolpaths and machining strategies. Even small inconsistencies can result in incorrect machining instructions or require costly manual intervention.

Visualization workflows are often more forgiving, but even here healing plays an important role. As soon as a model is reused for sectioning, measurement, or lightweight geometry generation, underlying inconsistencies can surface.

The key point is that healing requirements increase as workflows become richer. The more value a downstream application is expected to extract from a model, the higher the demands on geometric quality.

Healing for Hybrid Models in Mixed-Representation Workflows

Many real-world interoperability workflows involve more than precise CAD geometry. Tessellated data from scans, LiDAR, or manufacturing processes is increasingly combined with analytic models within the same dataset.

Mesh-based geometry presents unique challenges. Visual correctness does not guarantee topological validity. Issues such as holes, self-intersections, overlapping facets, and inconsistent orientations are common and can prevent reliable reuse of the data.

In these hybrid scenarios, healing must go beyond kernel-based correction.

Rather than attempting to fix mesh defects individually, global healing approaches reconstruct geometry from a volumetric representation. This makes it possible to resolve topological errors at a structural level and generate watertight, consistent models suitable for downstream use.

Volumetric and voxel-based techniques offer a controllable way to balance detail preservation and geometric robustness. They are particularly well suited to complex or noisy datasets where local repair strategies break down.

From an interoperability standpoint, effective healing must adapt to the nature of the data itself. Supporting both precise and tessellated geometry within a unified workflow is essential to making hybrid models reliable across engineering systems.

Programmatic Access to Healing and Why It Matters

Automatic healing during translation provides a necessary baseline, but it is rarely sufficient on its own for advanced workflows. Professional applications often need more control.

This is why programmatic access to healing functions is essential.

Through APIs provided as part of the 3D ACIS Modeler, developers can invoke additional healing routines beyond the default translation process. These routines enable custom workflows such as splitting edges, managing periodic geometry, or constructing non manifold topologies when required by the application logic.

This level of control allows OEMs and software developers to tailor healing strategies to their specific use cases rather than relying on a one size fits all approach.

At Spatial Corp, healing is treated as an integral part of the modeling workflow, not as an opaque black box. By exposing healing capabilities through well defined APIs, developers can integrate healing precisely where it adds the most value, whether during import, before editing, or prior to downstream processing.

Checking Before Healing: Diagnosing Model Quality

Healing is most effective when it is informed by diagnosis.

Before correcting a model, it is often critical to understand where potential issues lie and how severe they are. Checker functionality plays this role by assessing the geometric and topological integrity of a model and reporting problems before or alongside the healing process.

Diagnostics can identify issues such as invalid topology, continuity breaks, or tolerance related inconsistencies that may not be immediately visible. This information helps developers decide which healing steps are necessary and which can be avoided.

By combining checking and healing, workflows become more predictable and more robust. Instead of blindly applying corrections, applications can target specific problem areas and reduce the risk of unintended side effects.

From an engineering standpoint, this approach also minimizes downstream errors. Problems identified and resolved early are far less costly than those discovered during simulation, manufacturing, or late stage integration.

Performance Considerations and Healing at Scale

Healing inevitably adds computational overhead to the translation process. The extent of this impact depends heavily on the quality of the incoming model and the complexity of the geometry involved.

In large assemblies, performance considerations become especially important. Translating and healing every component sequentially can quickly become a bottleneck.

One effective strategy is to process parts in parallel. With assembly level workflows, individual components can be translated and healed independently, significantly reducing overall processing time.

Because some supported formats rely on third party components that are not thread safe, a multi process approach is often preferred over multi threading. While multi process execution introduces some communication overhead, healing workflows typically require little inter process communication. As a result, scalability remains high and performance gains are substantial.

This architectural approach allows healing to scale to complex, real world datasets without becoming a limiting factor in production workflows.

Healing as a Cornerstone of Trustworthy 3D Interoperability

As 3D models increasingly serve as the single source of truth across engineering workflows, their reliability can no longer be taken for granted. A model that moves between systems must do more than survive translation. It must remain geometrically coherent, topologically valid, and faithful to the intent of its original design.

Healing is what makes this possible.

By reconciling differences in tolerances, continuity rules, and geometric interpretation, healing ensures that translated models conform to the requirements of the target environment without altering their shape or purpose. It transforms fragile data exchanges into dependable engineering assets.

In modern interoperability scenarios, this function is no longer optional. Whether models are destined for editing, simulation, manufacturing, or advanced visualization, the quality of the underlying geometry directly determines the success of downstream operations.

At Spatial Corp, healing is approached as a core capability of professional 3D interoperability. Through robust translation technologies, advanced healing workflows, and programmatic access via APIs, Spatial enables software developers to build applications that users can trust with their most critical data.

When geometry becomes the specification, preserving its integrity is essential. Healing is the mechanism that makes that trust possible.

.jpeg?width=450&name=AdobeStock_289023609%20(2).jpeg)

.jpg?width=450&name=Application%20Lifecycle%20Management%20(1).jpg)